The monthly newsletters are an amalgamation of musings, two poems, and upcoming course and event announcements.

Listen via audio

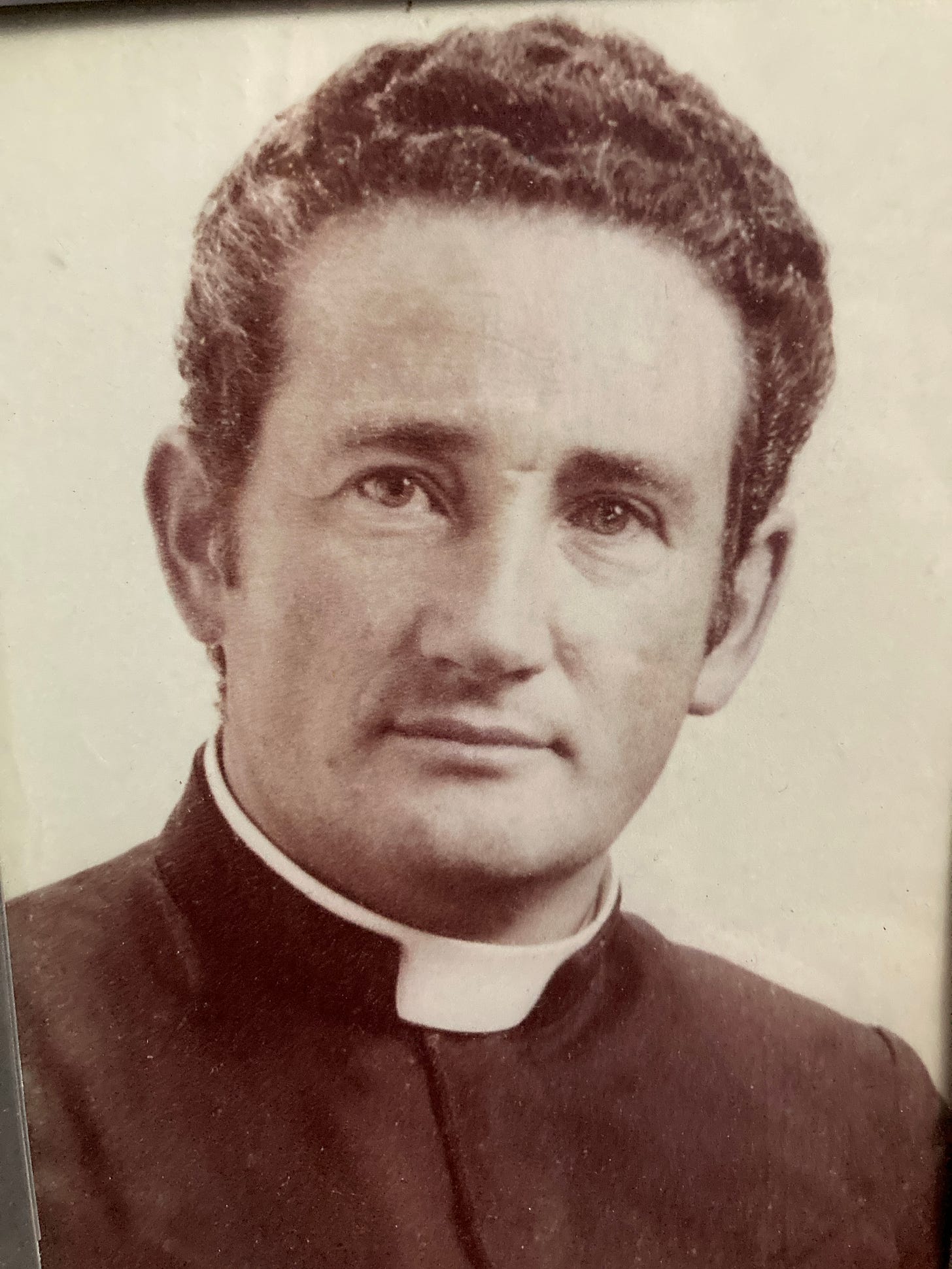

The priest died a day before my birthday. My father called to tell me the news. And across 10,000 miles, we shared a few moments in memoriam to his life. For those of you who have been reading my Substack for a time now, you might remember Don Luis - the Catholic priest who married my folks three decades ago, and who was the caretaker of one of the oldest books in Europe (you can read or listen to that entry here: Of Love and Books).

I didn’t reveal his name then to preserve his confidentiality, particularly because his custodianship of the book is pretty controversial in Spain. Many believe it should be in a museum or a private collection.

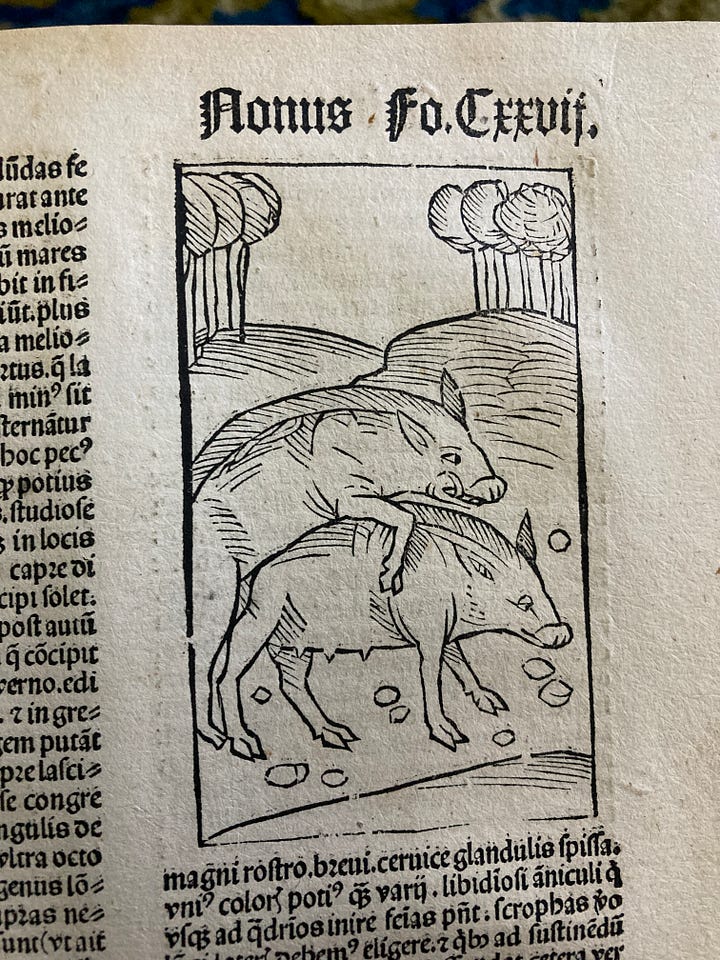

But Don Luis was a lover of beauty; not only in his magnificent collection of books and artwork, but the beauty in nature. I suspect he was also inclined to collect ancient artefacts in order to keep them safe. After all, we’re talking about a country that destroys national forests to build hotels. The only other copy of this book was burned by Franco’s soldiers during the Spanish civil war (book burning by the Falangists was common practice then). And this one would have certainly discomposed right-wing puritanism with its graphic images that taught how animals make babies (if you’re listening to this, it’s worth popping into the written piece to see some of the images I’ve attached - I imagine they would make Franco turn in his grave).

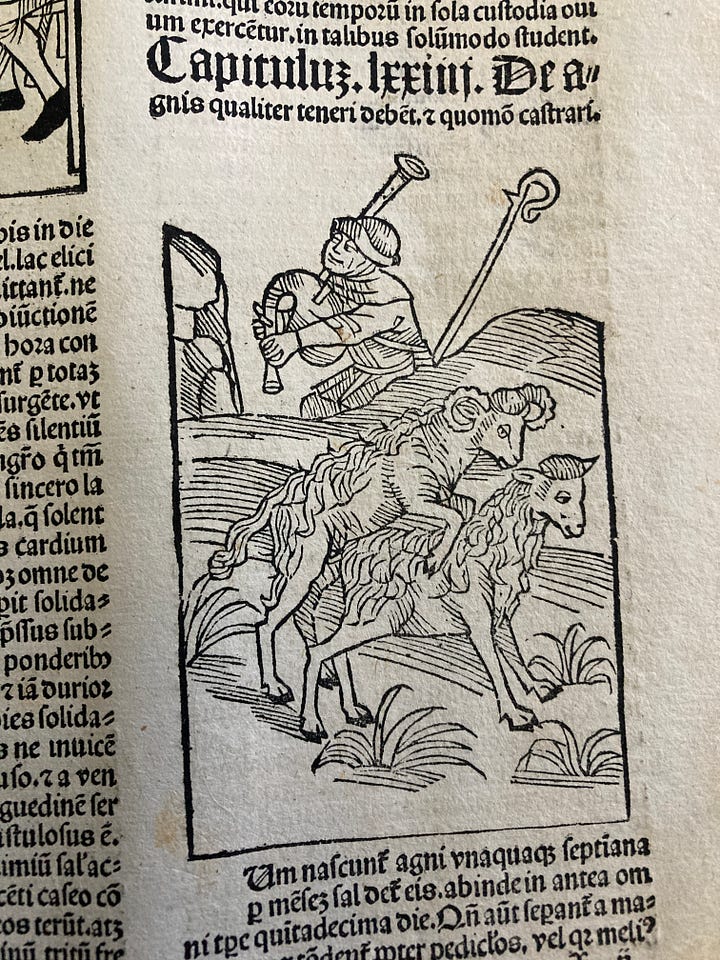

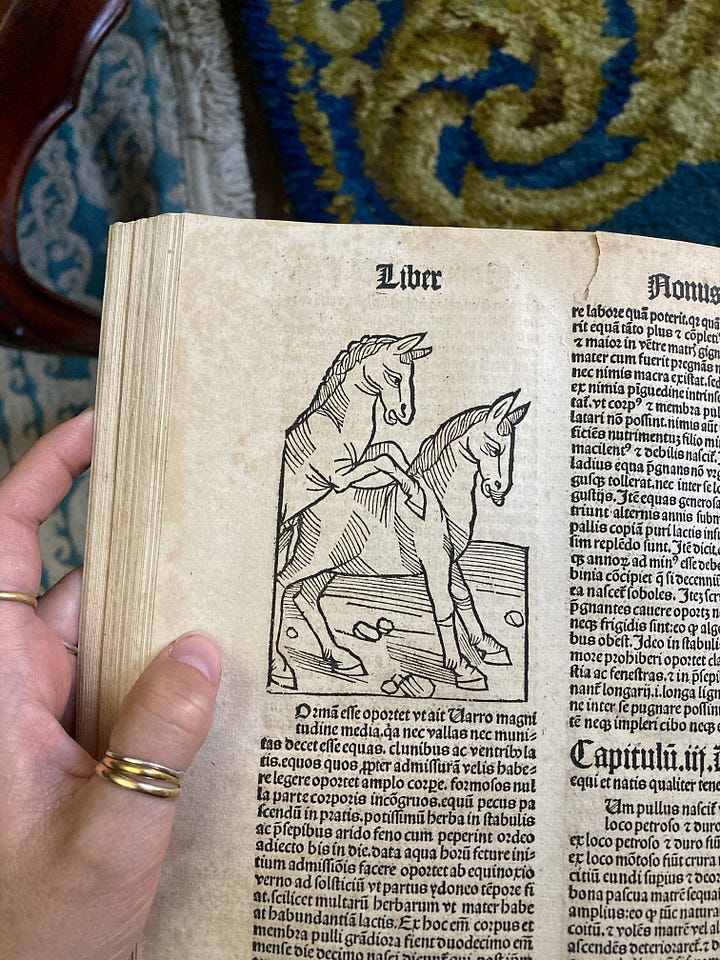

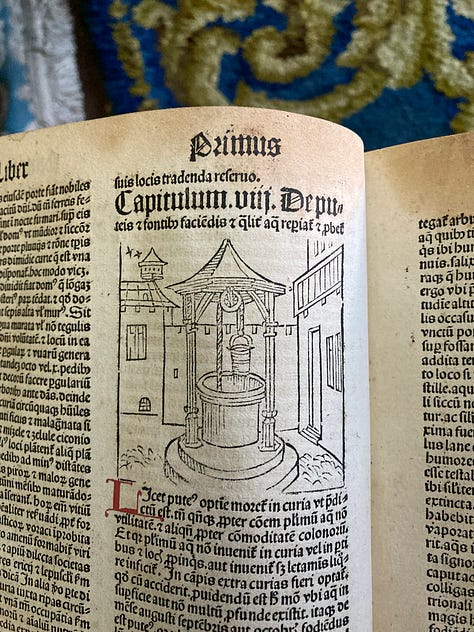

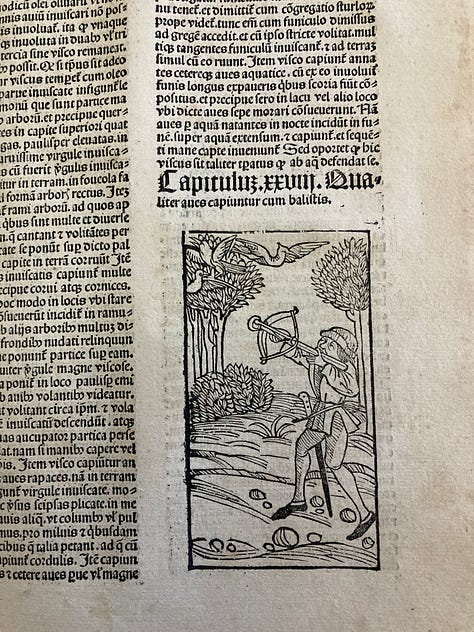

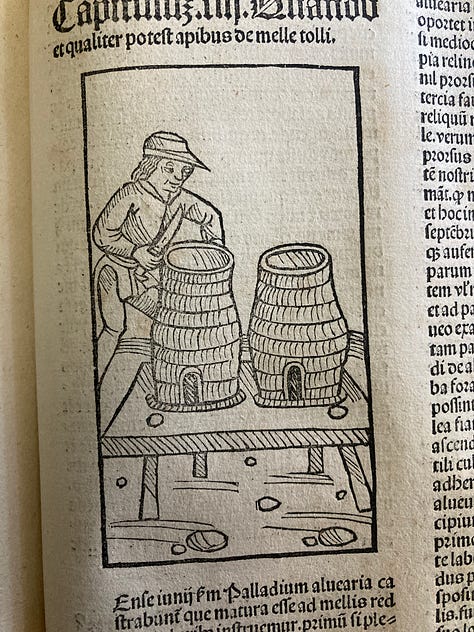

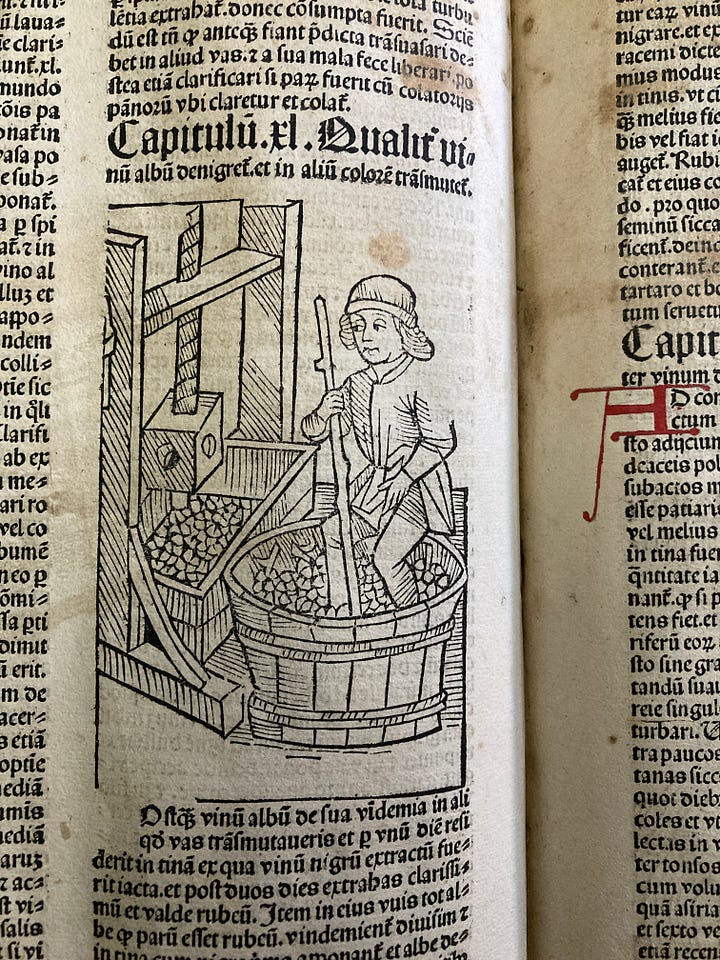

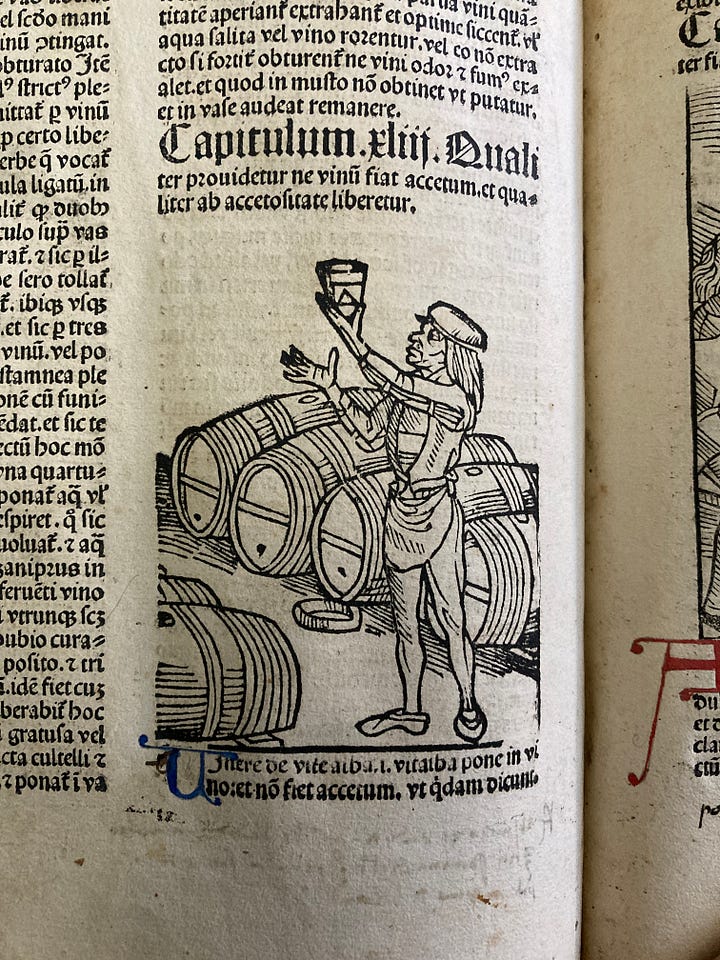

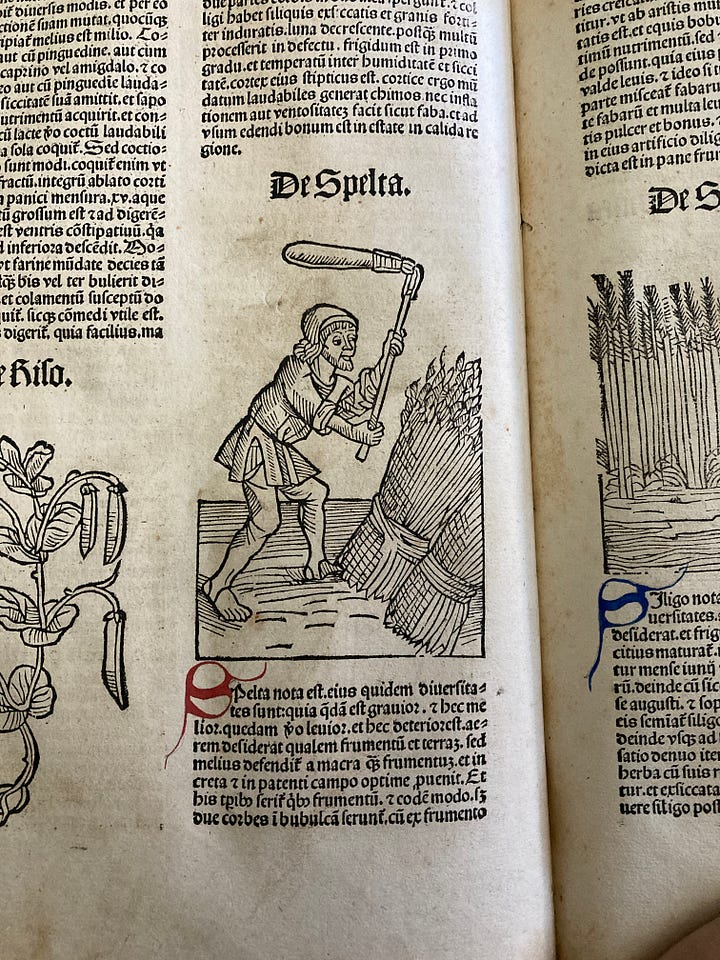

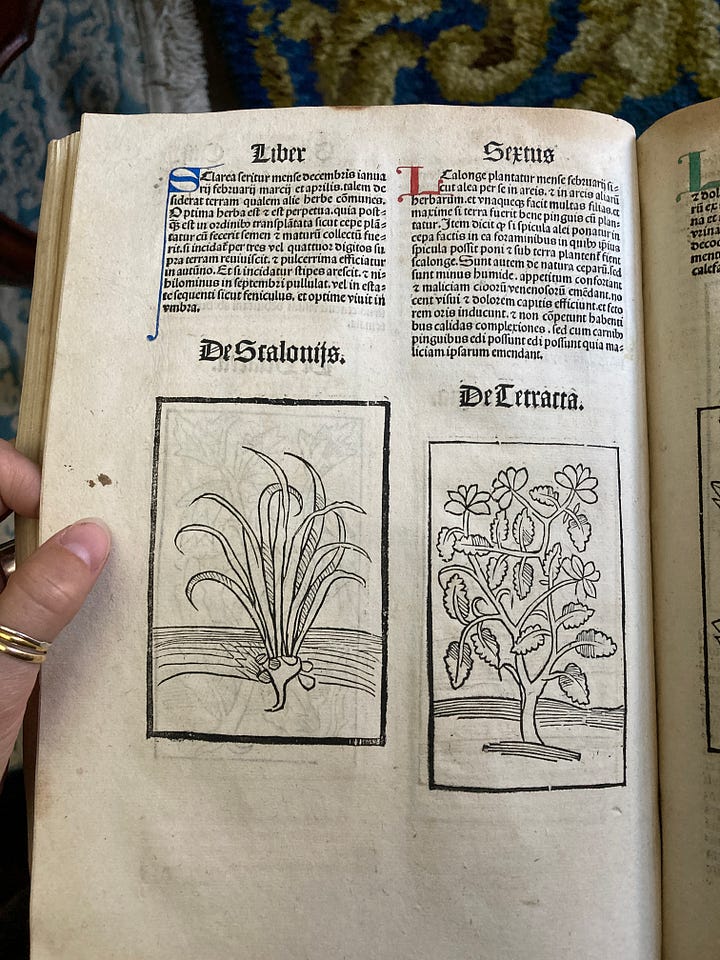

This book is known as an incunabulum - which essentially means it was printed in the first stages of printing in medieval Europe, between the 1400 and 1500s. Incunabulums were often instructional manuals. They offered step-by-step instructions on everything from the properties of local plants and how to use them remedially, to hunting, archery, haymaking, apiculture, viniculture, brewing beer, growing fruit and vegetables, digging wells and even falconry (some examples pictured below).

These manuals held the first written records of folk customs and practices. They were transcribed by Catholic priests in Latin. And so this incunabulum is precious as it was one of the first books to document and keep a record of the way of life and folklore of medieval Spain.

So it’s really no surprise that Don Luis chose to keep it safe in his home, along with his collection of artwork and other ancient manuscripts, much of which he saved during the civikl war. And though newspapers often called him the possessive and jealous priest because he wouldn’t give it up to the National Museum in Madrid, he would always open his doors to scholars. He believed in the importance of expanding knowledge. When I told him about the dissertation I was writing at the time, he told me of his wish that a thesis would be written on this book one day.

If you’re familiar with John Seymour’s work, this incunabulum could be understood as the medieval version of his book. It is essentially a guide on self-sufficiency. On living in a way that is responsible, Earth-centric and life-affirming.

Don Luis’ love of beauty, of books and artwork and nature, along with his awareness of the need for the modern world to reintegrate an Earth-centric philosophy is part of what elevates him - in my eyes anyway - to the status of a wise man. Or what indigenous cultures would call an “elder”.

An elder is a title bestowed on someone who has been recognised as a custodian of knowledge. They are individuals in society who hold a torch. This is very different to authority figures like politicians, government officials, the police or the clergy. Elders hold a different kind of office entirely. They don’t impose. They lead by example. They are like living libraries. Custodians of knowledge that they have often, though not always, received through a lineage. And they contribute to the betterment of society through knowledge.

‘For being a Catholic priest,’ my dad reflected during our call, ‘I never herd anything “Catholic” come out of his mouth.’

And it’s true. There was nothing dogmatic about Don Luis. And I think this is one of the central attributes that make an elder. Essentially, the art of sharing knowledge without imposing it.

His defiance of the dogmatisms of Catholic Spain always reminded me of the schoolteacher in one of my favourite films on the Spanish civil war called Butterfly Tongues. Here is the trailer (have tissues at the ready):

The last time I saw Don Luis, he was out on his balcony watering his flowers in his royal blue dressing gown, his hair tufty from an afternoon siesta. He was grumpy and in one of his colossal moods - the man sure had a temper. And he only perked up when I pushed him to bring down his incunabulum - again! - to flick through its heavy pages one more time. And as is the nature of loss, I can’t help but wonder what I might have done differently had I known this would be my last time with the priest and his book.

When you receive sad news, it only takes a few seconds to receive the information, but when you walk away, you’re walking into a totally different world. It is a sober reminder of just how tentative life is; the given world we think is so permanent, and the solid ground we think we are on, all so delicate.

Simone Weill knew it when she wrote, ‘Human existence is so fragile a thing and exposed to such dangers that I cannot love without trembling.’

My heart dropped to my stomach when I received the news. And I felt the trees in the Bush where I’m currently based close in a little, like the contraction of lungs on a long inhalation before holding the breath underwater. I plummeted into the watery liminality that you can only really access through encounters with mystical states, lovemaking, and sad news. It’s as though everything stops. Like the freezing of a clock’s hand just before it strikes midnight. A great pause in the pantomime that is our life.

And in that stillness the scythe of Death casts a threshold. And you can either look away, or take a step towards it like great fierce Seraphim facing the threat, encircling their huddled monsters of love, as D. H. Lawrence wrote.

When we think of the origin of the word “threshold”, it comes from “thrashen”, which means to separate the grain from the husk. Essentially, it offers us a choice to remain where we are, or to move into a more critical and challenging and worthy fullness. Thresholds are lines which separate two territories of spirit: who we are, and who we can become.

Death brings the possibility for change. It marks a threshold. And paradoxically, it is in service to more liveliness. To life. It has a way of making everything more vivid. More urgent. The funerary customs of classical antiquity and medieval Christianity knew it when they engraved their graves with momento mori, meaning “remember death”.

News of death can be awful and distressing. But when it is the death of an elder, there is an entirely other quality to it. It is monumental. And it feels like a threat of such vast immensity to the already fragile balance of things.

Because a torch goes out. And there are few and far between in our modern world. And the myths tell us it is the torch bearers that lead the way out of the Wasteland. How can we find our way out without them?

There have been many deaths of elders in the last few years: Malidoma Somé, Thick Nath Hanh, Michael Harner, Robert Bly, and most recently, Sinnead O’Conner.

The problem with the death of an elder in our culture is that we don’t have anyone taking their places. Knowledge lineages are breaking. There is no hand-down of power, or knowledge, fast enough to pick up the pieces of our broken world.

And what does a world without elders look like?

This is what the Inquisition, colonialism and the institutionalisation of folk and indigenous religious traditions had at their heart: the killing off of the elders.

Because elders hold an office. They teach personal accountability and freedom from oppression, both outer and self-imposed.

And how can you control a people who know themselves to be free?

Kill off the elders, replace them with self-appointed authority figures that uphold a particular agenda and worldview, and you have yourself the modern world.

While looking up what information I could find on what will happen to his precious collection and his beloved book, I found a maxim that a newspaper recorded him saying, which I think will be a sweet place to close for today. He said, ‘I have always thought that I will have completed my mission if when I go to bed, I have made someone smile, made them feel better, and above all, when at the end of the day, I have felt the smile of God.’1

Chin-chin to the wise ones.

Poetry Offering

As usual, here is a poem.

The Holy Longing, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. This version is translated from the German by Robert Bly. Tell a wise person, or else keep silent, because the mass man will mock it right away. I praise what is truly alive, what longs to be burned to death. In the calm water of the love-nights, where you were begotten, where you have begotten, a strange feeling comes over you, when you see the silent candle burning. Now you are no longer caught in the obsession with darkness, and a desire for higher love-making sweeps you upward. Distance does not make you falter. Now, arriving in magic, flying, and finally, insane for the light, you are the butterfly and you are gone. And so long as you haven't experienced this: to die and so to grow, you are only a troubled guest on the dark earth.

And lastly, instead of my own poem today, I would like to sing a Greek lament in honour of Don Luis, and all the elders who have gone away and who continue to teach us, even in death.

Song in the recorded version of this piece.

Announcements

Upcoming New Moon Rite: August 16th

Movement can be one of the greatest sources of support, healing and transformation. Once a month, on every New Moon, we seek to return to the body in a 90 minute guided movement meditation that draws on experiential embodiment practice and the exploration of altered states through dance.

Open to anyone who identifies as a woman or with the inner womb space.

8-9:30pm UK | £22

—

Upcoming Dismemberment Ceremony: Sunday August 27th

Initiatory teachings tell us that we must learn how to die to fully live. Spiritual deaths are ways of clearing the old debris we accumulate throughout life. In shamanism, a form of spiritual death is called dismemberment. Belonging to the family of “death mysteries,” it is a process of dissolution which may lead to renewal and a return “to the bones,” the essentials of being.

These ceremonies take place monthly, on the last Sunday of every month.

Open to all genders.

8-9:30pm UK | £22

What a beautiful heartfelt piece. I’m hugging you.