The monthly newsletters are a free offering to begin the month. I weave together musings, two poems (one by a published poet and one by me, as per a practice introduced to my master’s cohort by the poet Alice Oswald), reflections and all my upcoming course and event announcements. Thanks for being here!

Opening scene from Where do we go now?, a feature film by my all-time favourite director Nadine Labaki. A choreographed march in which a corps of black-clad Christian and Muslim women form a solemn, swaying procession to the cemetery. The same women gather regularly at the cafe to gossip and devise strategies to keep the men from fighting.

Women shriek. They tear their hair and clothing, scratch at their faces and beat their chests. They sway hypnotically and sometimes dance wildly, as if possessed. They scream out questions without answers, repeat themselves, call for vengeance. They will not be consoled. At times, their sobs, moans, and sighs compose themselves into song, into a searing melody or a mournful antiphony. They summon us to witness, but they seem mad. Unwashed and unadorned, they rub grime on their faces; they are alternately despondent and angry; they breathe unnaturally. They seem caught up in something both intensely sacred and dreadfully pagan, in an obscene exposure of women, their bodies, emotion: of the private in a public place. One is tempted to recoil, as if from contamination; one senses that the anguish will spread.

- Rebecca Saunders, And the Women Wailed in Answer: The Lament Tradition

Listen via audio:

Good morning,

I’m writing to you today from my home in Devon. The sun has finally come out after weeks of seemingly endless grey, and I’m poking my head out from a nasty flu that ended up dragging on for ten days.

It felt like a defeat.

In truth, I’ve been walloped by despair. Every morning since the genocide in Palestine began, my first emotion is dread. I have been finding it virtually impossible to continue on with life as normal.

It’s no doubt a social expectation that we must be able to disassociate ourselves both from our own emotions and from the tragedies of the world and get on with things.

The modern world is keen to repress emotional responses to ensure we continue to be functional agents in society; that we keep producing and churning the wheels of the machine.

But this doesn’t mean our emotions go away. They just get repressed.

We modern humans have become masters at repressing our emotions.

But in traditional cultures, there were - and continue to be in some parts of the world - customs to express this side of the spectrum of emotional experience. This custom is known as lament.

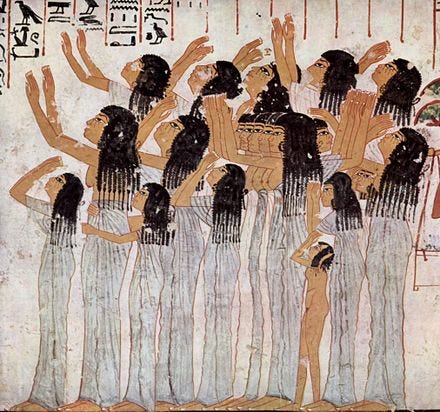

Lament was the way that suffering was made explicit. And the practice of lamentation was a specialised female function. In other words, the main responsibility to cleanse and transmute the violence, pain and sorrow of the world belonged to women.

Through the custom of ritual lament, it was women who wept for the fallen men of war, the killing of children, the deaths of loved ones…

By way of ritual processions, funerary rites, or weeping at the death bed of the deceased, lamentation was a means of purification, a public katharsis meant to cleanse and transform the suffering of those who are left behind.

In his Manifesto for Sanity and Soul, the grief literacy advocate Stephen Jenkinson (1954) writes, ‘Grief is not a feeling it is a capacity. It is not something that disables you, we are not on the receiving end of grief we are on the practising end of grief.’1

Ritual lament ensured that grief was fully expressed. It was a public display of pain for those who were suffering, but who were in the initial stages of grief that often causes us to dissociate and numb out.

From a shamanic perspective, this is a dangerous thing as it is when we are not fully inhabiting our bodies that we can experience intrusions in the form of illnesses, disease pathogens or “spirits” that can take residence in our bodies and cause us all manner of harm.

I can see how this practice could be unfathomably old, with its roots in the prehistoric cosmologies that were animistic and shamanic, and which understood that illness and imbalance is first and foremost energetic.

Ritual practice as a whole was a means of maintaining inner and outer harmony throughout the ancient world, and it continues to hold this function in traditional cultures and folk customs.

The work of women in these times was to ensure that the heightened emotions were released and transmuted into what might one day become wisdom. This is a deeply alchemical thing. And it brings to mind the alchemical operations of the medieval alchemists.

In alchemy, there are seven operations that, when looked at symbolically, refer to the transformation of the self. Tears are part of the operation of solutio, meaning dissolution. They represent a softening of the aspects of the personality that have hardened or become inflexible.

We weep to release, otherwise we will live our lives overwhelmed, consumed by our thousand-and-one worries and personal dramas and global catastrophes.

We need to be able to share our vulnerabilities. To express them. To collectively grieve. To give voice to calamity and pain and injustice. Lament is probably one of the most powerful expressions of grief we have.

In Ireland, the keening women, known in Gaelic as the mnàthan-tuirim, paid respects to the deceased and expressed grief on behalf of the bereaved family. Keening was a vocal lament for the dead undertaken by female mourners. It was an integral part of the whole process of grief and was performed either at the wake, funeral procession or interment. Keening was a social event; a grief ritual. And the women’s wailing was accompanied by the beauty of the Gaelic musical tradition.

Irish myth tells of female spirits known as banshees who are heard wailing at the onset of a death. Their apparitions are seen as an omen that foretells death is coming. Similarly in Welsh myth, the Gwrach y Rhibyn - which translated as the Witch of Rhibyn - also appears to give warning of an oncoming death through her shrieking, wailing or keening.

Eventually, the Catholic Church outlawed keening, dismissing it as a heretical pagan ritual.

In the Middle East, ululation is similar to the Celtic world’s keening. In Arabic, it’s called zaghārīt. Women’s ululations were wailing performances used in mourning but also in celebration, a noteworthy symbolic bridging between life and death.

Funerals in the Middle East to this day often have women accompanying the dead by wailing, pulling out their hair and beating their chests.

Funerary lamentation in Egypt is known as cidīd and has been women’s socially sanctioned expression of grief for millennia.

In myth, tears are often depicted as life-giving and are associated with new life and renewal. In an Egyptian creation myth, when the tears of the sun god Ra fell to the Earth, they transformed into bees. In the Odyssey, Odysseus weeps when he tells his story to the old sea people. His tears are those of a man who is finally remembering himself and stepping into new life. In ancient Greece, it was Aphrodite’s tears that bloomed into flowers when they landed on the ground.

In fairytales, tears are often redemptive. They cleanse a curse or heal when they fall on a body part. Rapunzel heals the prince with her tears. When the witch who has trapped her in her tower discovers that Rapunzel is being visited by a prince who climbs up the rope of her hair, she tricks him and, one night, as he climbs up, it is the witch that receives him. He falls into the thorn bush below and is blinded. He wanders lost for many years. And when he is finally reunited with Rapunzel, her tears fall into his eyes and restore his sight.

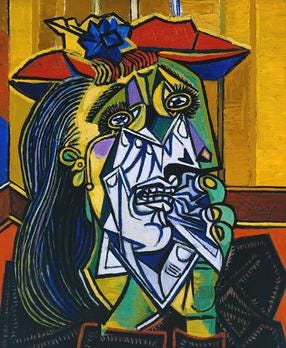

Tears release us from unknown depths of sorrow. Like rain, they fertilise the dryness and allow for new life. Picasso’s painting of the Weeping Woman during the bombing of Guernica represents a grieving mother weeping for the unspeakable grief of the survivors of the bombing, when Hitler's air force, acting in support of Franco, bombed the village of Guernica in northern Spain, a city of no strategic military value. It was history's first aerial saturation bombing of a civilian population. Sound familiar?

We are living through a similar time now; a time of unspeakable grief. At the time of writing this, it is Day 29 of the Genocide in Palestine. More than ten thousand Palestinians have now been killed, and over four thousand of them are children.

We haven’t seen anything like this in our lifetime. A genocide fully documented through social media by Palestinians on-the-ground, and shared this expansively by so many of us outside.

The news coming out of Gaza and the West Bank, filmed by Palestinian individuals and journalists on the ground, is jarringly at odds with what is shown on western media outlets. And we are noticing.

The narrative that caused the western world to dehumanise Palestinians in the first place is starting to crumble. Finally, we are beginning to see the true story.

I urge you not to look away now. We can’t afford to look away now. Keep speaking out, amplifying Palestinian voices, signing the petitions, writing to your MPs demanding a ceasefire, demonstrating, donating, boycotting, praying, documenting on your social media... We need to use all the resources at our disposal. The tipping point is now. We either move towards a free Palestine, or an eviscerated one.

Removing ourselves from collective ritualised lament has lead to a deep disassociation between our inner and outer worlds. We live as though world events that do not personally affect us are somehow separate from our individual lives.

That women can weep for us, can grieve for us, can move the energy of impossible suffering for us, casts us back to the old wisdom of an ensouled world. That the soul extends outside the body and we are all a part of that tapestry. And so I can weep for you. And you can weep for me. We can do this work for the Palestinians who are currently in full survival mode. We can be of assistance by transmuting the grief by spilling our own tears.

This is a devotional act. Lament is a devotion to life. Through it, we venerate and acknowledge the human experience in all its forms, the multitudes of who we are…

And so if you too have felt floored by despair and sorrow during this devastating time, ritualise it. Light a candle. Burn some herbs. Bring some intentionality to your pain. Let the tears flow out of you and see them as a cleansing fountain that washes the pain of the world and restores freshness and new life to the parts in us that have deadened with suffering.

Some Extra Resources

BBC Sounds Radio Programme - Songs for the Dead, Irish Keening

Songs - More Irish Keening

Article - How an Ancient Singing Tradition Helps People Cope With Trauma in the Modern World

Article - Weeping and Wailing in Chinese History: The Lament Cycle of Pan Cailian

Songbook - 99 Georgian Songs – A collection of Folk, Church and Urban Georgian

Book - Lamentation and Modernity in Literature, Philosophy, and Culture, by Rebecca Saunders

The opera piece Dido’s Lament expresses her profound grief when she is abandoned by her lover Aeneas-

Poetry Offering

This one is by Rumi, poet of devotion par excellence. An excerpt from ‘Delicious Laughter, Rambunctious Teaching Stories from the Mathnawi’ by Coleman Barks.

The cloud weeps, and then the garden sprouts. The baby cries, and the mother's milk flows. The nurse of creation has said, Let them cry a lot. This rain-weeping and sun-burning twine together to make us grow. Keep your intelligence white-hot and your grief glistening, so your life will stay fresh. Cry easily like a little child. Let body needs dwindle and soul decisions increase. Diminish what you give your physical self. Your spiritual eye will begin to open. When the body empties and stays empty, God fills it with musk and mother-of-pearl. That way a man gives his dung and gets purity. Listen to the prophets, not to some adolescent boy. The foundation and the walls of spiritual life are made of self-denials and disciplines. Stay with friends who support you in these. Talk with them about sacred texts, and how you're doing, and how they're doing, and keep your practices together.

—

And this next poem I wrote late one of these fevered nights.

Awake Dreaming

A meadow of wild flowers

moonlight, broken mirror petals

of poppies blood red

ochre of the caves

belly of Venus

full like the sea

at high tide

corn dripping gold

the only treasure

worth gathering

and the wrinkles

of cork trees

struck

with morning bird song

a lightning

that only the mouth

of Beauty can sharpen

and you in the night

weeping

for what, you know not. Announcements

As usual, I will be running the monthly New Moon Rite for women, and the Dismemberment Ceremony on the last Sunday of the month (open to all).

I will be teaching another online lecture for the Psychedelic Society this coming Monday.

And on Thursday I am teaching a month-long online course called The Three Secret Selves, meeting every Thursday for 2 hours.

Please scroll down for all the details.

—

UPCOMING CLASSES

Monday, 8th Nov: Online Lecture - When Women Were the Shamans: In the Neolithic Settlements of Old Europe | 2-hour lecture

Thursday, 9th Nov: Online course - The Three Secret Selves | 1-Month Course

—

UPCOMING MONTHLY EVENTS

New Moon Rite | November 13th, 8 - 9:30pm UK | £22

Dismemberment Ceremony | Sunday November 28th, 8 - 9:30pm UK | £22

Stephen Jenkinson, Die Wise: A Manifesto for Sanity and Soul

My grandfather followed the sound of a banshee across a field the night his young son left the body, but on another occasion I was actually saved by the same woman of the Sidhe when I was bitten by a brown recluse spider five times on my leg in my sleep. Not only did she awaken me in a terrible dream but also gave me the remedy in the same dream. The ensuing sickness over two years caused me to write an Irish trilogy. A Native American explained to me that spider medicine has everything to do with writing and bring the old back into the new. Many ancient families in Ireland have the banshee, a portent that is not always death but can be a life changer. X

Beautiful the ritual of Lament. Tears of the mother tears of the daughter. Alas my sister, in my part of the middle east we are no longer allowed to grieve. 'Haram,' my older cousin scolded me at my father's funeral five years ago, 'it is sinful to cry. It is the will of god. Wipe your tears.' I wanted to hit her with a chair. (I didn't). Our grandmothers ripped their hair and beat their breasts, our mothers cried and screamed, now we have to sit with shut mouths and crossed hands listening to the quran on tape (Don't get me wrong, there are some beautiful verses, but not all, as you know- things like punishment in the grave for example.) On the warring streets, we are made to rejoice the shahid. That's insane. Our bodies hold the grief. To think that in the old times we sat on the ground at the edges of graves, our vaginas kissing the earth, grounded, whirling our upper bodies in the lemniscat our arms as serpents rising - bleeding the pain into the mother - back to the mother - drinking up her healing love. To mourn together- cuts through ethnicity and faith - to dance for death and life. Perhaps forgiveness is found in collective ritual lamentation.

In these times of grief, Ive found being/working in nature to be healing (as I was glad to see you're doing too) - and another, which I almost forgot in sorrow - was dance - perhaps you did too. I hope not. I hope you're (always) dancing - through the sadness to joy. Thank you for the beautiful words and insights from under the Fig tree. It's wondedful to feel the resonance with others on this path. Blessed Bee.