Hello, friends. Again, a bit of a longer one today. These past newsletter topics are ones I feel deeply about, and clearly my pen gets away from me! As usual you can read or listen.

Listen via audio:

I believe in an animate world. By this, I mean that all living things have an intelligence and are intricately connected. Through this lens, the land itself has intelligence. And when I travel to new places, I make a point of introducing myself to that land and whoever caretook it.

In most cases, the caretakers are long dead. Missionary projects, colonialism, religious fundamentalisms and modernity have done a good job at killing off earth-centric traditions.

My methodology is, of course, highly controversial from an academic perspective. Soul plays no part in an academic setting whose god is called Data. I believe what my eye can see, kind of thing.

But, luckily I’m not alone in this endeavour. And when I first started out as an independent researcher, I had a mentor who ebbed me on even though it felt like swimming upstream. She is a mystic with a doctorate. Highly intellectual and yet in continuous communion with the spirit world. I won’t name her here out of respect as she is tremendously private.

When I first started out on this venture - this attempt to bridge the severing pull of intellectual ways of knowing on the one hand, and the direct, intuitive, sensuous and somatic on the other - she gave me what became a mantra that I carry with me always:

Walk with pen in one hand, veil in the other.

The veil is a metaphor for a way of seeing beyond that which is material. To carry both pen and veil is to approach a question holistically.

You can read more about my methodology in this past article below:

Having contextualised my approach, I want to tell you today about my encounter with the old aboriginal wisdoms of Tasmania.

A few weeks ago I went camping to that far away jurassic island off the coast of eastern Australia with my partner. I get terrible seasickness, so he took our car and tent across on the 8-hour ferry, and I flew in the next day.

The morning I landed, our car broke down and I had to make my own way from the airport across the northern side of the island to him. I found that the next bus in that direction wasn’t for another six hours, so I made my way to the closest town, found a map and, clocking a botanical garden, art gallery and historical museum, crafted a plan for myself.

The closest point was the art gallery, so I headed there first. And - as is the way with these things - ended up spending my six hours there.

Because as it turned out, there was an exhibition on the art and history of the aboriginal Tasmanians.

When I arrived into the exhibit, I felt the air thicken and the hairs on the back of my neck stand up. I immediately recognised that I was entering into a repository of knowledge guarded over by the spirits of the aboriginal ancestors, and whispered my prayers of acknowledgment and respect, before entering.

The presence of old spirits is common in museums that hold ancient artefacts. If it is true that we live in an animate world, then these artefacts of stone and seed and bone hold memory. And they speak to us.

My experience is the same in the archaeological museums of Serbia and Crete, the exhibitions of palaeolithic findings from caves in France and Spain, and even the British Museum on Friday evenings when it stays open late and everyone’s gone to the pub.

The old gods look over the forgotten worlds of our predecessors and tell their buried stories through song lines and myth lines that we can hear when we put our ear to the ground. In other words, when we listen with another kind of hearing.

As I walked through the dimmed room, I was amused by how things end up working out. A broken down car, a long wait for a bus, and a forced meeting with the imaginal elders of the land I had arrived to before I could enter it fully.

So, let’s begin with their creation myth.

Origin Story of the First Tasmanian

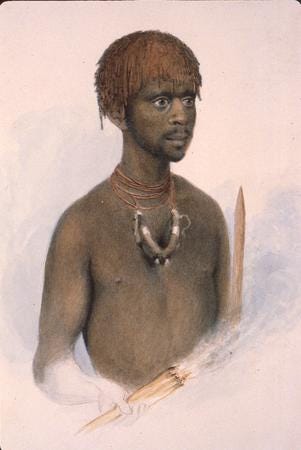

This story tells of Parlevar as the first Tasmanian aboriginal person.

There were once two brothers: Moihernee and Dromerdeenee. They lived in the sky. One day, they decided to make Parlevar, the first Tasmanian. First, they created him as a kangaroo. But because he had a tail and no knee joints, Parlevar could not sit down and had to sleep standing up. Moihernee’s brother Dromerdeenee helped Parlevar by cutting off his tail, placing grease on the wound, and making knee joints for him.

Parlevar stayed in the sky for a long time. Eventually, he came down the Milky Way and landed in Tasmania.

Moihernee was not happy that his brother had helped Parlevar. The brothers fought and, losing the battle, Moihernee fell from the sky and was turned into a stone for the rest of eternity. To this day it is believed that he is the megalithic rock in Cox’s Bight (southeastern Tasmania).

Doesn’t this remind you of the Greek myth of Prometheus?

For those of you who don’t know the story: Prometheus was a Titan, one of the ancient gods who existed before the Olympians. But unlike most Titans, Prometheus sided with Zeus during the great war between Titans and Olympians—and helped secure Zeus’s rule.

Yet, Prometheus’s heart remained with humankind. In the early myths, humans were fragile, fumbling creatures—living in darkness, vulnerable to cold, beasts, and death. Zeus wanted to keep it that way. He feared that if humans had too much knowledge or power, they would grow arrogant and challenge the gods.

Prometheus, whose name means “Forethought,” disobeyed Zeus and stole fire from the heavens—sometimes described as fire hidden in a fennel stalk—and gave it to humankind. With fire came warmth, cooking, light, metalwork, and civilisation itself.

This act was not only a gift—it was a rebellion. A symbolic awakening. Prometheus became a patron of humanity, a bringer of light, a challenger of divine tyranny, and can even be seen as the catalyst that made humanity conscious - is there anything more existential than contemplating a fire?

Zeus was enraged. To punish Prometheus for his defiance, he had him chained to a rock in the Caucasus Mountains, where an eagle—symbol of Zeus—would come each day to eat his liver. And because Prometheus was immortal, the liver would grow back each night. An eternal torment.

Prometheus remained bound for ages until, in some versions, he was finally freed by Heracles (Hercules) during one of his labours.

Interestingly, during part of our road trip, we listened to a podcast episode by the Blind Boy who happened to weave in the story of Prometheus. It’s well worth a listen!

The Cross-Cultural Fire-Bringers

These themes of defiance, creation, and punishment are cross-cultural in the creation stories of the mythic, oral tradition. It’s not just Prometheus and Moihernee who defy the other gods in service to humanity.

In Polynesian lore, Māui hides fire in his fingernails, steals it from the goddess Mahuika, and brings it back to his people—but not without being burned.

In Native American tales, Coyote risks all to steal fire from the gods— clever, agile, and half-divine, he is both punished and celebrated.

In the Yoruba tradition, Eshu stirs the pot of fate. He brings wisdom, language, and paradox. He plays tricks on gods and mortals alike, but always opens new paths.

In the Dreamtime of other parts of Australia, ancestral beings awaken the land through boundary-crossing acts—songs, footsteps, fire trails... They shape the world by stepping outside what was.

The First Tasmanians, Survival and Cultural Renewal

The original custodians of lutruwita (Tasmania) are known as the Palawa. They lived on the island for over 40,000 years, forming diverse nations and clans with deep spiritual and ecological relationships to the land, sea, and sky.

When sea levels rose around 12,000 years ago, lutruwita was cut off from mainland Australia. But the people adapted beautifully—developing unique technologies like fire management, shell middens, and stone tools specific to their environment. Their world was rich with meaning, ceremony, kinship, and Dreaming lore.

British invasion began in 1803, and what followed was one of the most brutal and swift acts of dispossession in human history. Colonists claimed the land as “terra nullius” (land belonging to no one), disregarding existing Aboriginal presence.

Between 1820 and 1832, violent frontier conflict—including massacres, abductions, and forced removals—led to what is now called the Black War. The Aboriginal population was decimated.

By 1830, most surviving Aboriginal people were forcibly exiled to Wybalenna on Flinders Island, in what was framed as a “protective” move by George Augustus Robinson. Conditions there were devastating, and many died of illness, grief, and malnutrition.

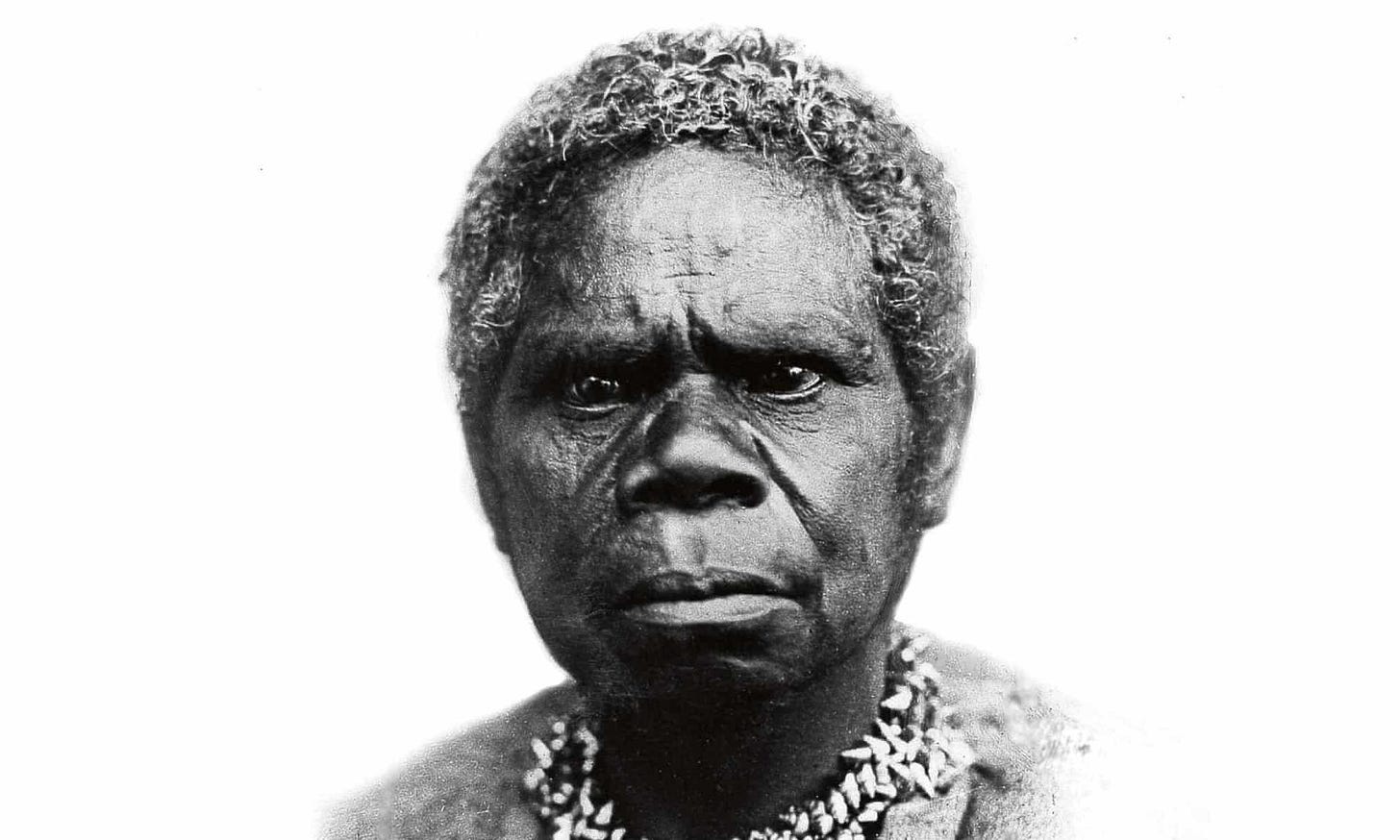

In the 19th century, it was falsely claimed that Truganini, a Palawa woman who died in 1876, was “the last Tasmanian Aboriginal.” This myth ignored the survival of many Aboriginal people through their descendants and the continuation of their culture in secret and in strength.

Tasmanian aboriginal women have continued the tradition of stringing cleaned and pierced maireneer shells onto cords of string. Some of these stringed shells have been found at sites dated from 1800 to 2000 years ago.

The Palawa had many ways to respect and dispose of their dead. Across much of Tasmania, the dead were seated in an upright position inside a hollow tree or on a funeral pyre. Ash from the pyre was rubbed on the faces of living relatives, so that their tears could mingle with the ashes of their loved one. In southeast Tasmania, people were cremated and the remains were covered by pointed bark tombs.

Tasmanian aboriginal people also remembered their dead by keeping parts of the deceased with them. Small bags of kangaroo skin were used to hold ashes or bones. A jawbone was sometimes worn around the neck as an amulet. Speaking the name of the deceased was strictly forbidden, and women would often break their shell necklaces as a way of mourning.

The Palawa have a continuing relationship with the land and its plants and animals. Selected trees were regarded as personally sacred, with particular species being significant to different clans.

Some of our knowledge of Aboriginal beliefs comes from early European records, especially those kept by George Augustus Robinson who, in the early 1830s, left detailed records of early Tasmanian aboriginal culture.

In his journal dated 2 July 1831, Robinson writes:

Those (tribes) of Oyster Bay… the gum trees they claim as theirs and call them countrymen. The stringybark trees the Brune call theirs, as being their countrymen, the peppermint the Cape Portland call theirs, and the Swanport claim the honeysuckle.

Some places in the landscape are seen as particularly important and are visited to this day for ceremonies and special events. Such places have stories associated with them that are passed down orally over generations.

The Belief in an Animate World: Humanity’s Oldest Spiritual Understanding

The belief that the world is alive and imbued with spirit—sometimes called animism—is widely understood by scholars and anthropologists to be the oldest known religious or spiritual tenet of humankind.

Before temples, before priests, before sacred texts, the first peoples of the Earth experienced the world as a living, breathing web of beings: mountains, rivers, trees, animals, winds… all were seen as ensouled, conscious, and communicative. There was no strict divide between “spirit” and “matter”; everything material was at the same time spiritual. Early humans lived in direct relationship with the cosmos—honouring the land, sun, moon, stars, and animals through ritual, gesture, and myth.

This worldview wasn’t considered “belief” in the modern sense. It was observation. It was relational. The world was not a resource to be used—it was a relative, a partner, a teacher and kin.

Palaeolithic cave art (~60,000 years ago) depicts animals, hybrid human-animal beings (therianthropes), and shamanic figures, suggesting that the earliest humans saw no boundary between species or worlds. Indigenous cultures across every inhabited continent preserve this view.

In Australia, the Dreaming describes a world continuously shaped by ancestral spirits. In subsaharan Africa, rivers, stones, and trees are understood as ancestors or spirit-beings. In the Americas, many tribes speak of the land as “people” and of humans as the “younger siblings” of creation. Early mythologies of Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece, and India still carry echoes of this older, animistic memory—before the later rise of anthropocentric, hierarchical gods.

Today, scholars such as Graham Harvey (author of Animism: Respecting the Living World) argue that animism is not primitive, but primary—the root from which all later religious expressions grew.

In fact, we could argue it’s not a religion at all, but a way of being; a reciprocity with the Earth; a spiritual ecology where every being has agency, dignity, and presence.

The belief in an animate world is not superstition. It’s bone memory. It’s relationship. It’s the oldest wisdom we carry.

In listening to the Palawa, I found myself stepping into a way of seeing that is at once ancient and urgently alive—a remembering that the world itself is animate, and that we are part of its dreaming.

Through their stories and customs, the Palawa trace a thread back to the first songs of the Earth—a time when every tree, every river, every stone was known to breathe, to speak, to feel.

Their living traditions remind us of a truth far older than history: that the Earth is not a backdrop to human life, but a living being we are bound to in kinship.

I would argue that the belief in an animate world is the oldest known religious tenet.

And with Australian aboriginal peoples roaming the land for some two thousand generations, their traditions are one of the oldest in the world.

Despite the trauma, Tasmanian Aboriginal communities never disappeared. Descendants of the Palawa have continued to fight for recognition, land rights, and cultural renewal.

Today, Palawa people are revitalising language, reconnecting with ancestral lands, reclaiming ceremony, and asserting sovereignty. Their resilience is a testament to the enduring strength of Aboriginal knowledge and spirit.

The traditions and customs of the Aboriginal world offer a living reminder that the world has always been experienced as alive. Their relationship with land, sea, and sky is not based on ownership or dominion, but on respect, reciprocity, and deep connection.

This animistic worldview reminds us that the Earth is not simply a backdrop for human activity, but a living network of relationships in which we participate.

At a time when modern cultures are grappling with ecological crisis and disconnection, remembering the world as alive is not just about honouring the past—it is about restoring a way of seeing that is vital for the future.

The Palawa, like so many Indigenous peoples, continue to carry this knowledge forward. Listening to them is not only an act of respect—it is an act of remembering what it means to belong to the living world.

Poetry Offering

This month’s poem is by Joy Harjo, a poet of Muscogee (Creek) Nation descent, whose work often centres on the living world and our relationship to it. The poem is instructional. It moves through layers of kinship with the natural world and belonging to life itself, linking personal identity to a larger web of existence.

Remember excerpt from She Had Some Horses, 1983 Remember the sky that you were born under, know each of the star’s stories. Remember the moon, know who she is. Remember the sun’s birth at dawn, that is the strongest point of time. Remember sundown and the giving away to night. Remember your birth, how your mother struggled to give you form and breath. You are evidence of her life, and her mother’s, and hers. Remember your father. He is your life, also. Remember the earth whose skin you are: red earth, black earth, yellow earth, white earth brown earth, we are earth. Remember the plants, trees, animal life who all have their tribes, their families, their histories, too. Talk to them, listen to them. They are alive poems. Remember the wind. Remember her voice. She knows the origin of this universe. Remember you are all people and all people are you. Remember you are this universe and this universe is you. Remember all is in motion, is growing, is you. Remember language comes from this. Remember the dance language is, that life is. Remember.

Announcements

APRIL 12 | Meeting the Bees and their Priestesses

I’m excited to announce my first in-person workshop in a long while! This will take place in Melbourne. If you’re local, here’s the info!

APRIL 27 | Monthly Ritual: New Moon Dismemberment

You can sign up for an individual ceremony, or for the next six months (and get 1 month free) to introduce more ritual into your life. This is the only ritual I am currently holding live.

Mentorship

This month, I have one opening for 1-1 mentorship. This is for anyone who would like support and/or supervision within both creative endeavours, spiritual work or personal support drawing on myth, stories, shamanic and animistic techniques for inner transformation.

These personalised sessions are structured to meet once a month for 3 months.

The Ochre Papers Advice Column

Here is the new landing page for the Ochre Papers advice column. Looking forward to receiving more of your questions!

NEW SERIES FOR PAID SUBSCRIBERS

And finally, a reminder that I’m launching a new series for paid subscribers. You can upgrade your subscription to receive each one to your inbox on the upcoming Sundays. Here is the first one:

As always, thank you for being here. If you enjoyed this piece, please do hit that “like” button and share it with your people. It makes the world of difference!

As always, such a joy to receive these posts on Sunday. This one truly resonated and had me looping back to our conversation from earlier this week. So grateful for it all 💝

Really wonderful to listen to your voice sharing this week. I was working in the garden and your message and words felt especially loud as my hands dug into the earth. I plan to share this and your other works with my children as the way you compile your information and express it is just incredibly wonderful. And so comprehensive.