Today Venus interrupts the weekly series on the world’s great mystics, quite literally!

Some of you may have heard about the Venus Retrograde lately. Though Instagram-priestesses have hijacked the “retrograde” word and it can taste like a crystal-shop or over-smoked sage, there is an old - and quite sensible - interpretation of this phenomena that might help nervous systems when this astrological event turns life belly-up.

Astrology might seem fluffy and New Agey now-a-days, but a grounded, more precise approach is possible. Ancient peoples throughout time have looked to the stars for insight. The stars provided a map, an archetypal context for the psycho-emotional struggles we wade through in our lives, and a means to orientate ourselves.

Today’s piece is intended as a care-package for the aftermath of the Venus Retrograde. And perhaps some insight into how to navigate it.

This one is free. Enjoy!

Listen via audio:

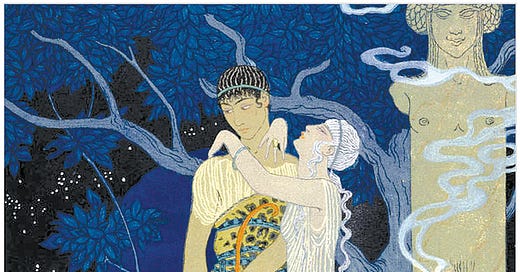

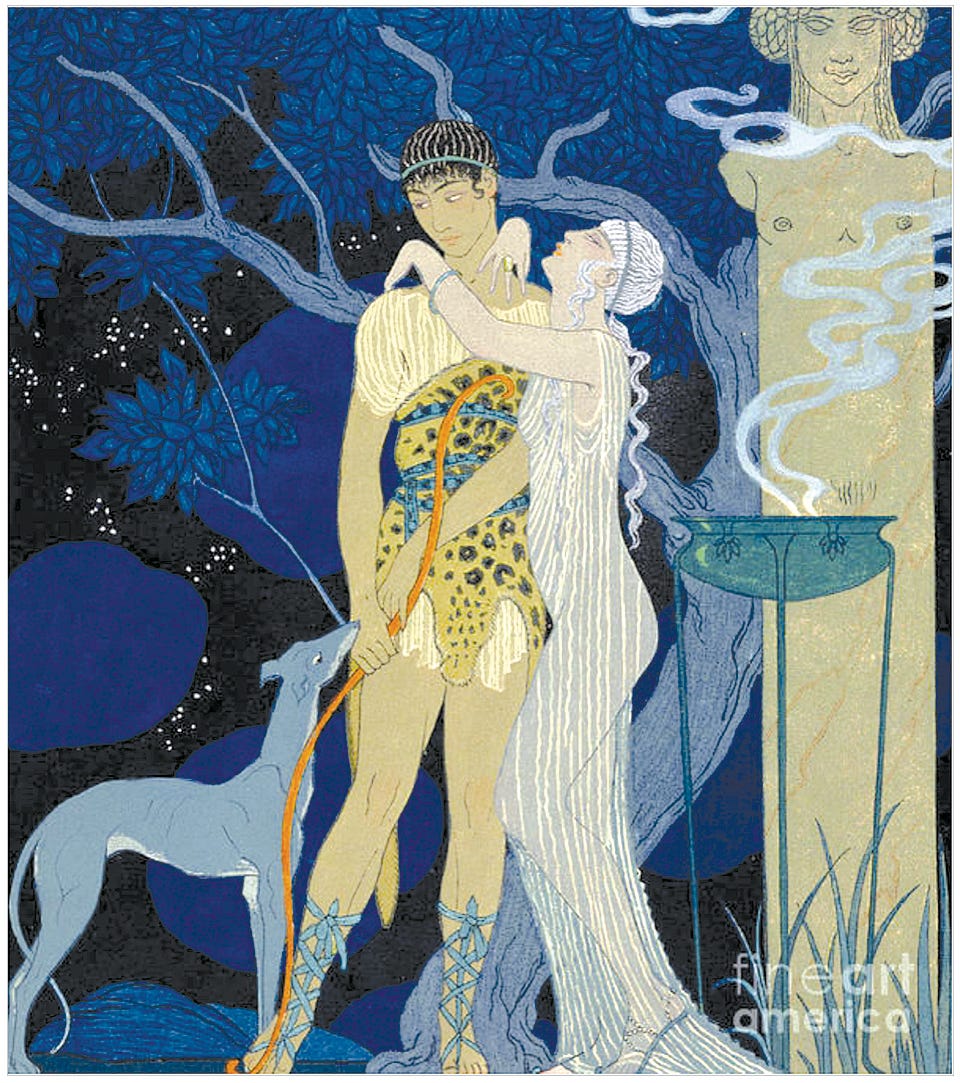

In one of the less-told myths of the ancient world, Aphrodite fell in love with a mortal: Adonis. One day while he was hunting in a forest, he was charged by a wild boar. The boar tore his thigh open. And Adonis bled to death.

In her grief, Aphrodite couldn’t remain among the feasts and laughter of Olympus. Instead, she descended into the shadowed realm of the Underworld to retrieve her beloved. Some say she pleaded with Persephone, Queen of the Dead, who had also laid claim to him. Others say Aphrodite went alone, guided by longing and defiance.

This descent was not an act of conquest, but of devotion. It was a movement not just toward loss, but toward truth, transformation, and the darker wisdom that love demands. When she returned with him, she emerged changed. Her beauty was no longer carefree, but tempered by sorrow. Her power was ripened. And just as the planet Venus vanishes from the evening sky and returns as the morning star, so too does this myth tell of the cycle love must walk: through grief, through shadow, and back into light.

Aphrodite was Romanised into Venus, a name her planet still carries.

When the planet Venus appears to slow down in the sky and move backwards—a celestial phenomenon astrologers call retrograde—something in us is stirred. Old lovers reappear. Long-buried griefs resurface. Beauty, love, and pleasure are questioned. This isn’t mere coincidence. Venus retrograde is a myth playing out in the sky: the descent and return of the goddess of love.

She must face death, endure separation, and plead for resurrection. Her descent is a journey of heartbreak, longing, and eventual return—a story that survives in ritual lamentations, seasonal rites, and the astrological dance of Venus through the heavens.

The result is a seasonal myth of renewal: her lover Adonis dies and is reborn, echoing the agricultural cycle of fertility and decay.

In ritual practice, particularly during the all-female Adonia festival in classical Athens, Aphrodite’s grief was enacted through song, mourning, and the planting of short-lived gardens.

While no single, canonical version of this myth survives in Greek epic, it appears in fragments across Hellenistic poetry, Roman mythology, and Near Eastern influence. Bion’s Lament for Adonis imagines her mourning and descent; Roman authors like Ovid and Apollodorus preserve variations involving Persephone; and Adonis himself is widely understood as a Greek echo of the Mesopotamian dying-and-returning god, Damuzi, whose goddess-lover, Inanna, descended to the underworld long before Aphrodite.

Though most people today associate the planet Venus with the Greek Aphrodite, the roots of her underworld journey stretch back thousands of years, to one of the oldest known myths of descent: the Sumerian tale of Inanna.

The Descent of Inanna: The Proto-Aphrodite

Long before Aphrodite arrived on the shores of Cyprus, she was known in ancient Sumer as Inanna, later as Ishtar in Akkadian. Inanna’s myth, inscribed on cuneiform tablets more than 4,000 years ago, tells of her deliberate descent into the underworld, ruled by her sister Ereshkigal. She adorns herself in the seven sacred garments of power—each a symbol of her divine authority—and passes through the seven gates of the underworld. At each gate, she is stripped of one item. By the time she stands before her sister, she has stripped bare.

Inanna is judged, killed, and hung on a hook. The Queen of Heaven dies. The world above withers. Crops fail. Desire ceases. And yet, this is not the end. Through ancient magic, her resurrection is orchestrated. Inanna returns, transformed. But her journey has a cost: she cannot leave the underworld unless another takes her place. Eventually, she chooses her lover Damuzi, who had not mourned her. He too descends. Thus begins the ancient cycle of descent, death, return, and renewal—a cycle of erotic power and sacrifice that underpins the seasons.

Inanna-Ishtar’s myth was inherited by the Cyprian goddess Aphrodite. Before she became the more light-hearted version we are familiar with in later Greek tradition, she carried traces of these older, darker stories.

Aphrodite’s descent here is not as detailed as Inanna’s, but the symbolism holds: the goddess of love confronts death. She grieves. She bargains. And she returns with something changed—less innocence, more depth. This cyclical grief, this passage between worlds, is what the Venus retrograde mirrors in the heavens.

Venus Retrograde as a Celestial Descent

This year, the Venus retrograde began in Aries and moved into Pisces—marking a symbolic descent from the realm of Ares, god of war and passion, into the domain of Poseidon, lord of dreams, mystery, and emotional surrender. This arc offers a potent frame: the goddess of love must journey from fire to water, from assertion to dissolution, confronting first the combative and egoic patterns of love, then yielding into compassion, longing, and spiritual truth.

Astronomically, Venus retrograde occurs roughly every 18 months, for 40 days and 40 nights. This year, it began on March 1st and culminated on April 12th. There is also what is known as a two-week pre-shadow and post-shadow period, which began around January 28th and will last until May 16th. This means that we are still being impacted by these archetypal forces and can orient ourselves accordingly. But more on that in a moment.

During this time, Venus disappears from the evening sky, draws closer to the Earth, and eventually rises again as the morning star. The ancients were acutely aware of this transformation. The Sumerians called Inanna “Queen of Heaven” not just as a metaphor but because she was identified with the planet Venus. Her dual appearance as morning and evening star mapped directly onto the phases of her myth.

To them, the retrograde cycle was not a symbolic backdrop but a sacred drama: the goddess descends, dies, and returns anew.

The number 40 is significant here. In the myth, Inanna's absence above brings drought and desolation, and her resurrection marks a return of vitality. Similarly, the 40-day Venus retrograde is often marked by a temporary withdrawal from romantic clarity, from aesthetic ease, from social charms. The goddess has gone inward. And we are asked to do the same.

Aphrodite Transformed: The Return

In many mythic and spiritual traditions, initiation follows a threefold path: separation, ordeal, and return. Joseph Campbell, in his study of the monomyth, described this cycle as the archetypal journey of transformation. First comes the call to leave the known world; then the descent into darkness, where trials strip away illusion; and finally, the return—with a gift of insight hard-won.

In the context of Venus retrograde, we might see these three phases mirrored in the planet’s journey. The pre-shadow phase is the separation, the retrograde itself is the descent and ordeal, and the post-shadow period is the return. We now remain within the post-shadow phase, which will continue until May 16. This is the time of return. It is not simply about moving on from what was uncovered during the retrograde, but about living with what was revealed—integrating the losses, recognitions, or insights gained. The myth of Aphrodite’s return reminds us that love after descent is never the same: it asks for new truth, presence, and a ripened form of grace.

When Venus turns direct—when she rises once again in the eastern sky as the morning star—it is as if the goddess has returned from her dark initiation. She is not the same. Her powers now include the ability to endure longing, to survive grief, to choose again from a place of knowing.

From April 12th until May 16th, we live out her return.

For those attuned to her cycle, this is a time of rebirth. Not a naïve return to love, but a conscious one. We remember what love costs, and we choose it still. As Martin Shaw asks: What do you love? What is the cost? And what are you willing to pay for it?

Perhaps in the ancient world, this myth served as a relational template—a sacred story teaching lovers how to stay with one another through cycles of light and dark, desire and grief. A story that told us what was required not only for the renewal of the land, but for the renewal of love.

A Myth for Our Time

In the modern spiritual landscape—so often flattened by instant gratification and performative healing—the myth of Aphrodite’s descent offers something far more enduring. It tells us that beauty is not always light. That love must go into the underworld. That true pleasure is earned. That the goddess of grace also knows grief.

As Venus emerges again, brighter each morning, we are invited to meet her with the wisdom of our own descent. To know what we now carry. To see where we are ready to love again—not from perfection, but from wholeness.

It can be helpful to turn to myths and the stars as maps for how to live. I don’t think we were ever meant to exist in a world without myths. Because the imagination works in story. So in the absence of collective, inherited, cultural myths that are passed down orally, we create our own stories and our own narratives. Many of which haven’t proved to be very generative.

We’re not free from the human need for a mythologised world. We need stories to live by, and to live up to and rub up against so that we can learn what we’re made of.

The western world doesn’t orient towards myth in the structured ways that ancient peoples did.

Religious behaviour was often the ritualisation of myth. In other words, the re-enactment of stories like the Myth of Return of the vegetations god that dies and resurrects, or the myth of the Great Mother Goddess who gives and takes life…

Myth and ritual interpreted the mysteries of the natural world and the human soul. They gave people a way to orient themselves.

So what happens when we stop undertaking the rites that emulated those myths in order to make sense of our place in this world? What happens when we don’t have a literacy for the change in seasons and the movements of stars that, as it turns out, influence our inner lives just as much as they do the outer world?

I sometimes wonder how people live in periods like the astrological one we’ve just moved through that have been so complicated and demanding of us without these maps. Is this why suicide rates are so high around February/March in the Northern Hemisphere? Is there something else going on that our soul needs a language for and that destroys us when we don’t have it?

What happens when we lose our myths? When we don’t have rites that emulate those myths - which is how we make sense of the world and ourselves - by re-enacting and ritualising them…

If you believe in the eternal nature of the soul - I don’t mean when we all had past lives as Cleopatra or Genghis Khan (much more likely I think is that we were peasants or foxes or a particular turn in a river bed); but if it is true that the soul is eternal, then we would have lived through times that saw a mythologised world. We would have lived in those times more than we haven’t, as eternal souls.

So now, when there are these colossal stories like the one of the Goddess’ descent - which have defined ancient cultures for millennia, not just decades but thousands of years when people’s entire cultural identity and religious sensibility was based on these stories… we don’t remember how to navigate them.

Those stories are based in ecological, astrological, cultural, psychic and soulful occurrences that continue to happen, they didn’t stop just because we became mythologically ignorant; they continue on all the same, whether we are aware of them or not.

And so that is a question I think should be paramount in our lives: how do we mythologise and ritualise our lives so that we know how to live in the world?

We can’t just say we’re part of everything and then carry on our merry way. If we’re part of everything, then the trajectory that Venus makes in the sky every 18 months is going to have consequence on our lives. And we can either participate with her, or withdraw.

I really do wonder how we survive without knowing these stories. Because even knowing them still feels like we are put in impossible circumstances, and yet we have to survive.

The American novelist Toni Morrison talks about how when we go through these ordeals, we rarely return whole. We return in part. The majority of us has died. Somewhere along the way it was too painful, and the majority of us has not come back from these ordeals. When we return in part, all we can do is continue to live. There’s no more energy or capacity to go back and try to retrieve those lost parts. The only way is forward.

Here is an excerpt of her talk:

I interpret what she says as the importance of respect as a fundamental principle in times of upheaval and suffering. That a guiding torch, or a compass in such times, is to orient towards a way of life that we will have respect for.

In other words, what can you do that will conjure respect for yourself? And that can be a guiding star going forward?

Otherwise, it is so easy to get lost in the tangled web of despair, frustration, longing, fantasy, shame or regret.

Aphrodite draws everything out into the light. There is no hiding.

The importance of a mythologised world and a ritualised life can’t be undervalued, particularly in these big moments that in the ancient world would have been marked by festival and ceremony, the community getting together, undertakings rites that were uncomfortable and strenuous that would last days and involve fasting, or sacrifice, or drinking psychedelics or long periods in isolation…

Part of the role of these stories is that they ground us and remind us where we belong in the great chaos.

Toni Morrison advises we orient towards respect - behaviours that are going to conjure a sense of self-respect. I would also add respect for our loved ones. To not put them in situations that are going to bring out more of their pain, and in consequence of that, bring out certain behaviours that can make us lose respect for them.

The way I personally experience Aphrodite’s descent is that we actually have very little agency. We think we’re participating, but actually she’s just tearing the house down. And there’s nothing we can do about it. So we can either go down easy or go down hard. Either way, she’s taking us down.

So the more appropriate response perhaps is to let it happen. To say: lay me down easy. I’ll go of my own free will.

If we don’t have a literacy for the archetypal context here, if we don’t know what’s happening, we’ll kick and scream. We’ll fight it because we’re built to survive. When you watch any kind of animal documentary in the wild, the intrinsic instinct of all living things is to survive.

Any animal of prey will fight tooth and nail to the end to survive.

And yet the one thing that drives us - which we find in all the myths - is that we are here to consume. It’s not a “love and light” spiritual truth, really. The way life survives is by consuming. Otherwise it becomes death. Life consumes in order to live.

The Trickster is such a precise personification for this. In so many of the myths, all Trickster wants to do is eat and fuck. It’s all food and sex.

Life consumes. Life is here to eat other life forms. That’s what we do. I think that’s why so many spiritual traditions have the creed of non-violence at their heart. They recognise that to live means we must cause harm, because to live is to consume, so how can we do it in the least violent ways possible?

So to tie that into Aphrodite, there’s this pull towards consumption. We will be taken down and we will be consumed by she who is greater life. She is life incarnate. And we can either fight for survival like an antelope in the paws of a lion, or we can offer our neck and allow the predator to have her way with us.

And now, that’s done. And maybe next year we’ll do it better. Maybe a way we move towards the principle of respect is by making a commitment to remember this next year. And to hold ourselves a bit more elegantly through it. With a little more grace. Acknowledging that there’s no stopping it, but there is agency in how we show up; how we meet the underworld descent.

I think the more aware we are of these stories, the more chance we have of holding ourselves respectfully.

If we know the requirements of the gods to live in this world, maybe, we’ll start to do it a little better.

This was a very interesting read and so well written! really enjoyed it <3

Thank you for this. This was just the thing for me to read right now—for personally as well as heavenly reasons.