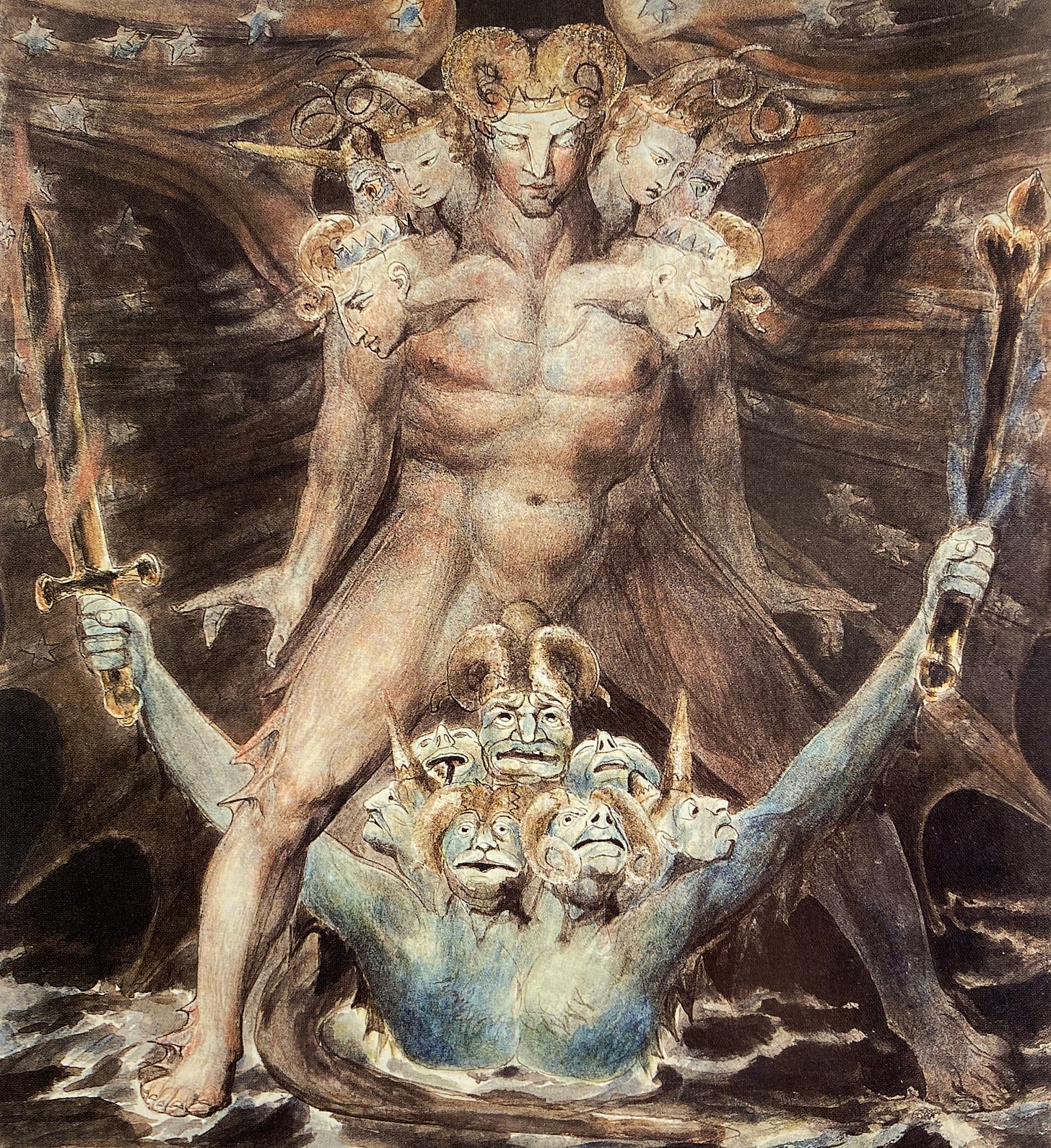

To Yield Yourself to a Dream

(Part 2) | The Lost Language of the Imagination in the British Romantic Era

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Under a Fig Tree to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.