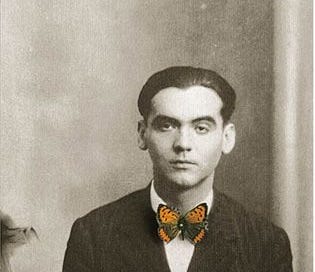

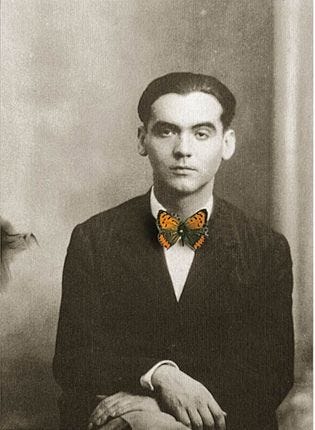

On Lorca: Perceptions of a Poet

Essay (Part 3) | The Lost Language of the Imagination in Spanish Surrealism

This piece is part of a collection of essays I am writing on the Imagination in different cultures and schools of thought. And so this essay is best understood when read as part of this series, as I may make references to concepts mentioned in previous essays.

Please note: All Lorca references and quotes are my translations.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Under a Fig Tree to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.